Inizia "la corsa al mare"

“La corsa al mare” non è uno scontro per la supremazia marittima, come parrebbe; e non é nemmeno una competizione sportiva dilettantesca.

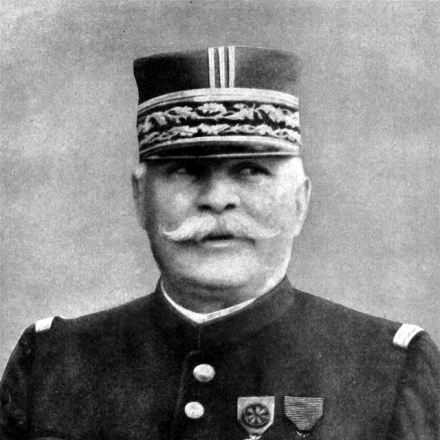

Il Generale Joffre, Comandante dell’esercito francese, ha avuto un’intuizione brillante: continuare a dare capocciate al muro non è una buona soluzione; bisogna trovare un’alternativa ai continui attacchi frontali. A sud-est, con la Svizzera di mezzo, c’è poco da inventarsi. Joffre rivolge dunque la sua attenzione a nord: vuole aggirare il fianco nemico con una manovra avvolgente. Perfetto.

Sì, ma c’è un problema: anche il nuovo Capo di Stato maggiore tedesco, il Generale Falkenhayn, sta cercando una possibile svolta. E anche lui fa la stessa pensata: aggirare i francesi a nord. Il risultato sarà la cosiddetta “corsa al mare”.

A nessuno riuscirà la manovra; si fermeranno una volta giunti alla Manica, ormai bloccati dall’acqua oltre la sabbia, costretti a guardarsi in faccia per buoni quattro anni.

Al fronte la situazione resta in stallo; il maltempo non agevola le operazioni. I combattimenti più duri sono nelle Argonne, ma il 16 settembre i tedeschi entrano a Valenciennes.

A Vienna anche i comunicati ufficiali si fanno meno deliranti, nonostante la parola sconfitta sembra non essere conosciuta. Tutte le ritirate avrebbero uno scopo strategico. Difficile da credere.

Diversa la situazione nei giornali, per forza di cose intrisi di propaganda.

Nonostante l’inferiorità numerica, l’esercito asburgico continua a resistere nei pressi di Przemsyl. E di questi tempi può essere considerato un successo.

Davide Sartori

GLI AVVENIMENTI

Politica e società

- L’Inghilterra chiede l'intervento armato del Portogallo.

Fronte occidentale

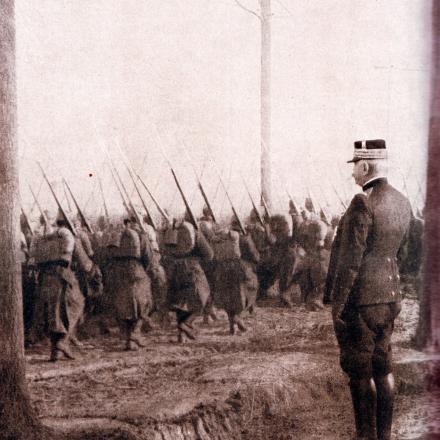

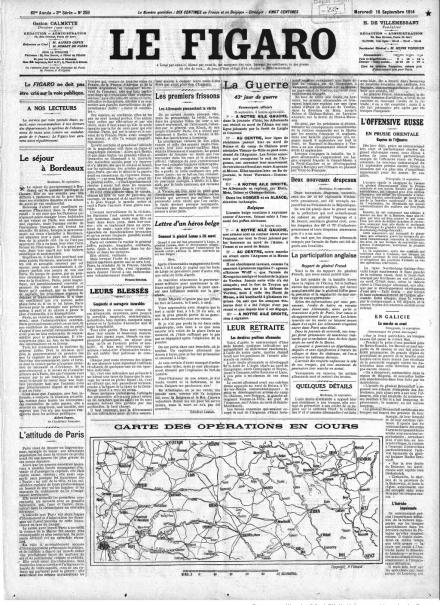

- Aisne: il Generale Joffre abbandona gli attacchi frontali e prepara un piano per colpire il fianco destro tedesco. Sta per cominciare "la corsa al mare".

- I tedeschi entrano a Valenciennes.

- Violenti scontri nelle Argonne tra francesi e tedeschi.

Fronte orientale

- Galizia: si continua a combattere nei pressi di Przemysl.

Parole d'epoca

James Patterson

Diario dal fronte

I have never spent and imagine that I can never spend a more ghastly and heart-tearing 48 hours than the last. Not a moment in which to write a word in my diary. We have been fighting hard ever since 8am on the 14th and have suffered much.

At about 6am at Moulins we hear a good deal of firing going on and shells begin dropping about. We are then on the road moving north. The Queen's have been re-directed to the north-east some little time before and we are head of the Brigade.

The 2nd Brigade is already engaged and we are sent to the high ground to the left to assist them. As we go we get some six shrapnels at us but mercifully are not touched. We reached the shelter of the high ground which rises quickly and steeply from the plain and then we advance over the crest and take up our position in a wood, ready to move out when required. Shrapnel and rifle fire fairly heavy.

The first casualty is my mare who was shot in the head. Nothing very bad at present and she is able to go on carrying my stuff. Though I do not ride her. The General and Staff and CO and I watched the fight in the neighbouring valley in front.It is a high ridge opposite, i.e west of us, that we have got to go for and nasty work it will be.

Jenkinson, the Brigade Major, is killed, poor fellow, and soon afterwards we begin to suffer in the wood, chiefly from ricochets.

We get several men down with small wounds, and then as C Company goes to attack, Lieutenant M T Johnson of A shot through the body. We hope he is not mortally wounded, but feared he is. C, D, and A Companies go out, leaving B in support.

Swarms of the Germans on the ridge, rather massed. Our guns opened on them at 1800 yards, and one can see a nasty sight through one's glasses. Bunches of Germans blown to pieces.We again suffered some casualties and eventually had to retire, or rather the Companies which have gone out have to come back to our ridge again. Here we stay firing and being fired at for some 8 hours and then another effort. Meanwhile our guns are having a huge duel. Not much success, and Germans are too numerous to really push back properly. Richards is hit in the arm and leg.

Nothing very bad I fancy. Several men killed. At dusk we are ordered to move up the valley towards the T of Troyon, which we did. As D Company was leading the wood a melanite shell burst at head of 1 Platoon. Poor young Vernon and a few men were knocked out. Vernon mercifully and miraculously not killed. On we go. It is now too late to be fired at by rifle fire and we go on well, but in the dark C and A Companies go ahead, and D lost touch.

Most annoying. On reaching the ridge at the head of the valley we find only B and D companies, and as we were looking for the others, shots rang out and we were soon at it again. Short and sharp. Germans withdrew.I have a horror of a night firing. One is so very likely to kill one's own men, and from wounds I have seen since, I am sure some of them were hit like that on this very occasion.

The Brigadier and his staff came along and rode right past us, and in a few minutes they were fired on. General and Staff Captain of an Brigade Major, and one or two NCOs and men have got away, the rest were missing the next morning and have just been found by some of our search parties some distance ahead of our position. They have been fed by the Germans and looked after, but have been there for two days. We then spent the night in trenching our position, and at dawn a force of enemy was seen advancing. One of the officers called up to us that he wished to speak to an officer, but after the episode at Landrecies with the Guards, we weren't having any of that. I have no doubt that they really did wish to surrender but they must do it properly as one man did this morning and march up with his hands above his head and no arms upon him. So we opened fire, and although we lost some men we wiped them out at 200 yards, and there they lie in front of us.

Poor devils. Later on the enemy's guns enfiladed us. We were told we were to hang on at all costs, and at all costs it had to be. We lost severely and it was a very bad business.We were cheered on about midday by a message from Field Marshal French to say that we of the 1st Division had saved the situation and by holding on had allowed the crossing of the river to be made. Since then we have been under fire of all sorts, rifle fire from snipers, shell from enemy, shell (bursting short) from our own guns and we have not lacked experience. I am thankful that I and my particular friends have not taken a knock yet, but there is lots more to come. However, we have done and shall continue to do, please God, what we have to do and that is all about it.

The sights were ghastly. Wounded crying all night for help and no one to help them. The doctors have done all they can, but the casualties are ever heavier than they can easily cope with. We have had a good few German prisoners and many Germans wounded have come through our hands, poor fellows, absolutely done and half-starved. I am certain that given a reasonable excuse they will surrender en bloc.

Our total casualties are Yeatman and Johnson killed, Richards and Vernon wounded, and of the R & F 18 killed, 76 wounded and 122 missing, of whom I trust many may be found alive and well, as one must always lose some in the dark.Here I sit outside our headquarters trench in the sun. The rain which we have had without a break for the past two days has now stopped and the world should look glorious. The battle has stopped here for a bit although in the distance we can here the 2nd English Army Corps guns and their battle generally. As I say all should be nice and peaceful and pretty. What it actually is is beyond description. Trenches, bits of equipment, clothing (probably blood-stained), ammunition, tools, caps, etc etc, everywhere.

Poor fellows shot dead are lying in all directions. Some of ours, some of the 1st Guards Brigade who passed over this ground before us, and many Germans. All the hedges torn and trampled, all the grass trodden in the mud, holes where shells have struck, branches torn off trees by the explosion. Everywhere the same hard, grim, pitiless sign of battle and war. I have had a belly full of it.

Those who were in that South Africa say that that was a picnic to this and the strain is terrific. No wonder if after a hundred shells have burst over us some of the men want to get back into the woods for rest. Ghastly, absolutely ghastly, and whoever was in the wrong in the matter which brought this war to be, is deserving of more than he can ever get in the world. Everyone very cheery and making the best of things. Men of course wonderful, as T. Atkins always is. I must try and write to mother now.