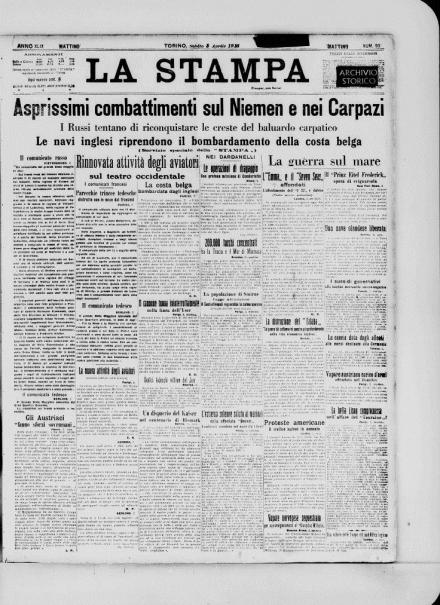

L'esecuzione di Sergei Myasoedov

L’incubo dello spionaggio preoccupa tutti i belligeranti. Il 3 aprile Pietrogrado trova il suo colpevole: con un comunicato ufficiale l’Alto Comando russo annuncia l’esecuzione del tenente colonnello Sergei Myasoedov, impiccato per le «relazioni con agenti di una potenza nemica».

L’ufficiale faceva l’interprete per lo Stato Maggiore della decima armata, stanziata al confine con la Prussia orientale. È accusato di aver contribuito alla grande avanzata tedesca di inizio anno. Stando al processo, Myasoedov intratteneva relazioni personali persino con il Kaiser e da prima del conflitto.

In Galizia i russi patiscono una battuta d’arresto: dopo la conquista di Cegielka l’offensiva nei Carpazi viene bloccata. Lo stallo segue tutta la linea meridionale del fronte; a Chernivtsi si registrano scontri durissimi, ma non se ne cava un ragno dal buco.

Qualche buona notizia arriva dal Mar Nero: l’incrociatore turco Medjidia viene affondato da una mina, mentre la flotta russa è sulle tracce del Goeben e del Breslau.

Davide Sartori

GLI AVVENIMENTI

Politica e società

- Un comunicato dello Stato Maggiore russo annuncia che il tenente colonnello Myasoedov, interprete presso lo Stato Maggiore della 10ª Armata, processato per relazioni con gli agenti di una Potenza nemica, è stato impiccato.

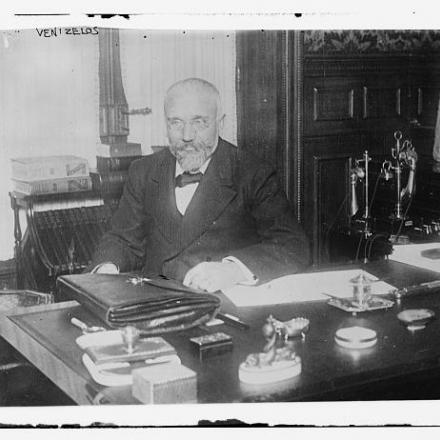

- Grecia: pubblicazione del primo memorandum di Venizelos al Re Costantino riguardante la politica estera greca.

Fronte occidentale

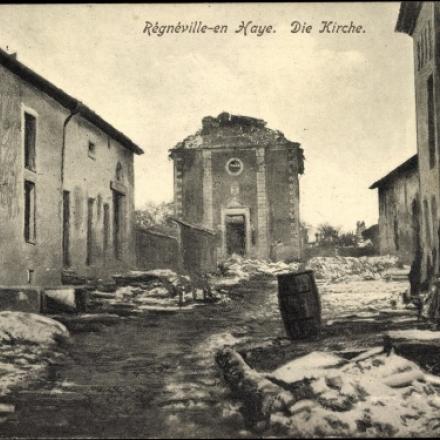

- I francesi prendono Regniéville (Woëvre).

Fronte orientale

- Respinto l’attacco russo nei Carpazi.

- Duri scontri a nord di Chernivtsi.

Fronte asiatico ed egiziano

- L’Expeditionary Force francese comincia a sbarcare ad Alessandria.

Fronte d’oltremare

- Le forze sudafricane attaccano Warmbad (sud ovest dell’Africa tedesca).

Operazioni navali

- L’incrociatore turco “Medjidia” affondato da una mina al largo di Odessa; la flotta russa del Mar Nero ingaggia in combattimento il “Goeben” e il “Breslau”, senza grossi risultati.

- Completato lo sbarramento nello stretto di Dover, a largo di Calais.

Parole d'epoca

Primo memorandum di Venizelos al Re Costantino

pubblicato il 3 aprile 1915

Athens, January 11, 1915.

Your Majesty,

I now have the honor to submit to your Majesty the contents of a communication which the British Minister here made to me with instructions from Sir Edward Grey.

Greece, by his communication, is again confronted with one of the most critical periods in the history of the nation. Until to-day our policy simply consisted in the preservation of neutrality, in so far as our treaty obligation with Serbia did not oblige us to depart therefrom. But we are now called upon to participate in the war, no longer in order to fulfil simply moral obligations, but in view of compensations, which if realized will create a great and powerful Greece, such as not even the boldest optimist could have imagined only a few years back.

In order to obtain these great compensations great dangers will certainly have to be faced. But after long and careful study of the question I end with the opinion that we ought to face these dangers.

We ought to face them chiefly because, even though we were to take no part in the war now, and to endeavor to preserve our neutrality until the end, we should find ourselves exposed to dangers equally serious.

If we allow Serbia to be crushed to-day by another Austro-German invasion, we have no security whatever that the Austro-German armies will stop short in front of our Macedonian frontiers, and that they will not be tempted as a matter of course to come down as far as Salonica.

But even if this danger is averted, and we admit that Austria, being satisfied with a crushing military defeat of Serbia, will not wish to establish herself in Macedonia, is there any possible doubt that Bulgaria, at the invitation of Austria, will advance and occupy Serbian Macedonia? And if that were to happen, what would be our position? We should then be obliged, in accordance with our treaty of alliance, to hasten to the aid of Serbia unless we wished to incur the dishonor of disregarding our treaty obligations. Even if we were to remain indifferent to our moral de-basement and impassive, we should by so doing have to submit to the disturbance of the Balkan equilibrium in favor of Bulgaria. That Power, thus strengthened, would either now or some time hence be in a position to attack us, when we should be entirely without either a friend or an ally. If, on the other hand, we had, in the circumstances indicated, to go to help Serbia in order to fulfil the duty incumbent on us, we should do so in far more unfavorable circumstances than if we went to her assistance now, because Serbia would already be crushed, and in consequence our aid would be of no, or at best of very little avail. Moreover, by rejecting now the overtures of the Powers of the Triple Entente, even in the event of victory we should secure no tangible compensation for our support in their struggle.

Let us now examine under what circumstances we ought to take part in the contest. Above all we must seek the cooperation not only of Roumania, but if possible of Bulgaria as well.

If we should succeed in obtaining this co-operation through an alliance of all the Christian States of the Balkans, not only would every serious danger of local defeat be averted, but their participation would bring a most important influence to bear on the struggle of the Entente Powers. For it is no exaggeration to say that their participation would exercise an important influence in favor of the ascendancy of the latter.

In order that this may be brought about, I think we should make adequate concessions to Bulgaria. So far we have refused even to discuss any concessions whatever by us to Bulgaria. Not only that but we have declared that we should emphatically oppose any important concessions by Serbia which might disturb the balance of power established in the Balkans by the Treaty of Bucharest.

So far this policy has obviously been the only one to follow. But now matters have changed. The instant that visions open out for the realization of our national aims in Asia Minor, it becomes possible to consider some concessions in the Balkans in order to secure the success of such a far-reaching national policy. To begin with we should with-draw our objections to concessions on the part of Serbia to Bulgaria, even if these concessions extend to the right bank of the Axios (Vardar), and if these concessions do not suffice to induce Bulgaria to co-operate with her former Allies, or at least to induce her to extend a benevolent neutrality to them, I would not hesitate, however painful the severance, to recommend the sacrifice of Cavalla, in order to save Hellenism in Turkey, and with a view to create a real Magna Grasecia which would include nearly all the provinces where Hellenism flourished through the long centuries of its history.

This sacrifice, however, would not merely be the price of Bulgaria's neutrality, but would be in exchange for the active participation of Bulgaria in the war with the other Allies. If this suggestion of mine were accepted, the Powers of the Triple Entente should guarantee that Bulgaria would undertake to buy the property of all those inhabitants of this ceded district who wish to emigrate within the boundaries of Greece. At the same time it would be agreed that the Greek population living within the boundaries of Bulgaria should be interchanged with Bulgarian population living within the boundaries of Greece, each State respectively buying their properties. It would be understood that this interchange of population and the purchase of their properties would be carried out by a Commission consisting of five members, one member to be appointed severally by England, France, Kussia, Greece and Bulgaria. The actual cession of Cavalla would only take effect after the fulfillment of all these conditions. In this way a definite ethnological settlement in the Balkans would be arrived at and the idea of a confederation could be realized, or, at any rate, an Alliance with mutual guarantees between the States which would allow them to devote themselves to their economic and other developments, without being primarily absorbed almost exclusively in the task of strengthening their military organization.

At the same time, as a partial compensation for this concession, one would ask that, if Bulgaria extend beyond the Axios, the Doiran-Ghevgeli district should be ceded to us by Serbia, so that at least we could acquire, as to Bulgaria, an adequate boundary, since we should be deprived of the present excellent one to the east (of Greek Macedonia). Unfortunately, on account of Bulgaria's greed, it is not at all certain that, whatever concession we make, we shall be able to satisfy Bulgaria, and lead her to co-operate with her former allies. If we cannot obtain Bulgaria's co-operation, then it would be important that we should at least secure Koumania's co-operation, for without this co-operation our joining in the war would be hazardous.

My opinion that we should respond to the suggestion put before your Majesty, with a view to our participation in the war, is also actuated by other motives. In fact, if we remain impassive spectators of the present struggle we not only run the above-mentioned dangers, which the crushing of Serbia will create against us. For, even if a fresh invasion of Serbia were abandoned and Austria, with Germany, should turn their efforts to coming out victorious in the two principal theatres of the war, in Poland and in Flanders, again the danger for us would be great, first, because if they were victorious they would be able to impose the same changes on the Balkans which I have previously indicated as possible results in the event of Serbia's defeat.

Beyond that, their victory would mean the death-blow to the free life of all small States, besides the direct damage which we would suffer through the loss of the islands (the Sporades). And again, if the war did not end by a decisive superiority either of the one or the other, but by a return of the status quo ante helium, still, after such a conclusion of the war, swift and sure would come the complete destruction of Hellenism in Turkey. Turkey coming out invulnerable from a war which she had braved against the three big Powers, and emboldened by the feeling of security which her alliance with Germany would give her an alliance which clearly will last in the future, for such seems Germany's aim will complete at once and systematically the work of destroying Hellenism in Turkey, driving out the population without pretext and in masses, and appropriating their possessions. In this she will not only find no opposition from Germany, but will be strengthened by her, inasmuch as Germany will be glad to get rid of a competitor for Asia Minor which she (Germany) covets. The driving away in masses of hundreds of thousands of Greeks living in Turkey will not only destroy these, but drag down in financial ruin the whole of Greece.

On account of all these reasons I conclude our participation in the struggle, under the above conditions, to be absolutely imperative. It is fraught, as I previously stated, with serious danger. But, unfortunately, for us to keep any longer aloof offers also grave danger, as I have said above. As against the dangers to which we shall expose ourselves in taking part in the war, the expectation soars above all a legitimate expectation, I hope that we may save the greater part of Hellenism in Turkey, and that we may create a great and powerful Greece. And even if we do not succeed, we shall at least have our conscience at peace with the conviction that we have struggled to save our race from slavery, that worst of dangers, and fought for the good of humanity and for the liberty of small nations, which German and Turkish rule would irretrievably endanger. And last, even if we fail, we shall preserve the esteem and friendship of powerful nations those, indeed, who created Greece and so often since have helped and supported her. While our refusal to fulfill our obligations to our ally Serbia would not only destroy our moral standing as a State, and would not only expose us to the above dangers, but would leave us without friends, and destroy all trust in us in the future. Under these conditions our national life would be endangered.

Your Majesty's most obedient servant,

EL. K. VENIZBLOS.