L'Intesa decide di non decidere

Quando gli interessi geopolitici contrastano con le possibilità militari, il problema si fa spesso insolubile. Tutta l’Intesa è cosciente del grave rischio balcanico; il punto non è neanche decidere “come” intervenire, ma “se” intervenire.

Già, perché politicamente esistono fin troppe ragioni per aiutare la Serbia. Se il piano tedesco funzionasse, la Germania aprirebbe la via per Costantinopoli, romperebbe il blocco economico, potrebbe inviare o ricevere rinforzi e munizioni dalla Turchia e isolare la Russia. In più, abbandonare l’alleata Serbia significherebbe, per l’Intesa, dire addio a qualsiasi influenza su Grecia e Romania. Non si fiderebbero.

L’intervento nei Balcani sembra quindi scontato, ma una domanda se la pongono in tanti: “L’Intesa è in grado di sostenere, in tempo utile, lo sforzo militare necessario?”

La questione è dunque molto più complessa: la volontà politica deve vincere lo scontro con la fattibilità.

Servirebbe un esercito di circa mezzo milione di uomini, comunque non meno di 350.000. E dovrebbero essere già addestrati, non reclute; anche perché si avvicina l’inverno e le montagne serbe non sono un terreno facile. Quindi servono uomini pronti, mezzi, rifornimenti, una logistica impeccabile e un piano d’azione ben preparato. Al momento l’Intesa non ha nulla di tutto questo.

A Parigi, Londra, Pietrogrado e Roma ci sono dei buontemponi ricchi d’ottimismo: “Tempo una o due settimane e siamo pronti”. Evidentemente non tutte le settimane durano solo sette giorni. Le stime più realistiche parlano di almeno un paio di mesi, ma per quella data gli austro-tedeschi potrebbero essersi già congiunti con i bulgari e allora sarebbe tutto più complicato, forse inutile.

Non c’è soluzione al problema: comunque la si guardi, una campagna balcanica è militarmente un incubo; si rischia un “Dardnelli-bis”.

E proprio da Gallipoli arriva un monito indiretto: il 14 ottobre il Generale Hamilton viene destituito; gli Alleati hanno preso coscienza del fallimento e studiano la “exit-strategy”, ma il Comandante non accetta l’idea, è ancora convinto di poter vincere.

Ma torniamo nei Balcani, perché l’Intesa deve fare la sua scelta, ma decide di non decidere: continuano gli sbarchi “alla spicciolata”, si va avanti con quello che si ha, sperando in un miracolo, l’improvviso intervento di Grecia e Romania in supporto. È una scelta rischiosissima, potrebbe significare una condanna a morte per decine di migliaia di soldati.

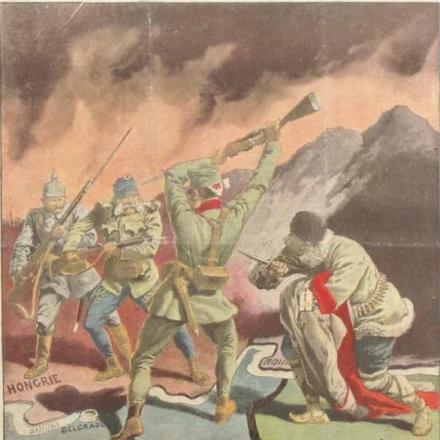

E intanto la Bulgaria ufficializza la dichiarazione di guerra alla Serbia.

Davide Sartori

GLI AVVENIMENTI

Politica e società

- La Bulgaria dichiara guerra alla Serbia, forze bulgare attaccano il paese da est.

- Approvato l’incremento delle forze armate degli Stati Uniti.

- Discorso sulla politica inglese di Sir Edward Grey.

- Ordinanza pubblica dell’autorità tedesca: chiunque abbia il tifo deve dichiararlo alle autorità o rischierà fino a tre anni di carcere.

- Il Generale Sir Ian Hamilton viene destituito. Il Generale Sir William Birdwood prende temporaneamente il comando dell’Expeditionary Force del Mediterraneo.

Fronte orientale

- Duri combattimenti a Illukst (Dvina); austro-tedeschi fermati sullo Strypa (Galizia).

- Nella regione di Tarnopol (Ternopil’) i russi sfondano tre linee austro-ungariche.

Fronte meridionale

- Gli austro-tedeschi assaltano Požarevac; i bulgari avviano l’invasione della Serbia e attaccano sul fiume Nišava.

- L'esercito serbo, pur cedendo terreno, contrasta il passo agli avversari, specie a sud di Smederevo.

Operazioni navali

- L'E-19 affonda cacciatorpediniere tedesco vicino Faxö.

Parole d'epoca

Voglia d'uva

di Cesare Ermanno Bertini, Sergente Maggiore

Monfalcone (GO)

Un casetto curioso del quale io ed un soldato ne siamo protagonisti mi ha fatto trascorrere la giornata più veloce delle precedenti.

Erano diversi giorni che mi era venuto il desiderio di andare in cerca d’uva della quale io sono ghiotto moltissimo. Siccome qua la frutta che si mangia durante i pasti è ben diversa da quella di buon gusto benché la diano gratis: pallottole, granate da 149 con contorno di shrapnels da 75: è da immaginarsi con qual desiderio mi sarei sgranellato un bel grappolo d’uva.

Sapendo che fuori delle nostre trincee, in prossimità di quelle nemiche, vi sono dei vigneti, ho deciso di andarvi. Senza pensarci su due volte ho chiamato Leoncini, soldato della mia squadra, ed in sua compagnia sono uscito quatto quatto dalle trincee.

Appena fatti circa 200 passi abbiamo scorto l’uva alla quale abbiamo subito dato l’assalto con gran coraggio.

Per la fretta che avevo mangiavo uva, grappoli e foglie ma ho smesso subito perché mi sono sentito tanto gonfio da scoppiare come una granata da 305.

Allora si che sarei stato fresco: ci sarebbe stato il caso che mi fosse saltata una gamba a Vienna un’altra a Roma e la testa a Pisa. Picchiando una nasata contro il campanile e facendolo pendere del tutto.

Mentre tranquillo me ne giravo pel vigneto, una scena si svolgeva in trincea. Le vedette, scorgendoci da lontano, avendoci scambiato per due soldati nemici, hanno dato l’allarme gridando: “Ci sono due austriaci, forse si vorranno arrendere”.

In fretta e furia il Capitano fece schierare un plotone entro le trincee; poi fece uscire 19 uomini comandati da un Tenente ed un sergente per farci prigionieri.

Essendoci stato fatto cenno di arrenderci ci siamo avvicinati: indescrivibile è stata la scena che è successa quando mi hanno riconosciuto.

I soldati risero, rise il Capitano, rise il Tenente che dalla rabbia mi lasciò andare due pugni sul naso.

Subito dopo il tramonto uscii di nuovo dalle trincee assieme al soldato Leoncini e Marioni coi quali sono andato, col permesso del Capitano, in ricognizione verso i piccoli posti nemici!

Si ringrazia il gruppo L'Espresso e l'Archivio diaristico nazionale di Pieve Santo Stefano

DAL FRONTE

Sul Mrzli (Monte Nero) la sera del 13 riparti di nemici tentarono un' improvvisa irruzione contro i nostri approcci giunti ormai in stretto contatto con le posizioni dell' avversario.

Il tentativo è fallito con gravi perdite.

Sul Carso, nel pomeriggio del 12, l' avversario, dopo avere eseguito un violento fuoco di artiglieria e fucileria, accompagnato dal lancio di numerose bombe a mano, a notte fatta attaccava le nostre posizioni a est di Monfalcone.

Di fronte al fermo contegno delle nostre truppe e falciate dai nostri tiri efficaci, le fanterie nemiche ripiegarono in disordine sulle proprie linee e lasciarono sul terreno molti cadaveri e nelle nostre mani dei prigionieri.

Firmato: CADORNA

Events in Balkans

Sir Edward Grey, Ministro degli Esteri inglese

Discorso in Parlamento del 14 ottobre 1915

With the leave of the House I shall make the statement which the Prime Minister promised a few days ago would be made this afternoon. I am, of course, going to make a statement not on the military but on the diplomatic side of the situation. I am aware that many criticisms have lately appeared in some quarters of the Press upon the conduct of diplomacy since the War, and especially with relation to the Balkans, but I do not propose to touch upon those in any way, not because I think there is nothing to be gained from considering criticism or because I think that no answer could be given, but, as the Prime Minister has suggested, it is a somewhat delicate time to have discussion, and I propose to confine myself to a bare statement and short résumê of the general objects of our diplomatic policy in the Near East since the opening of the War, making as little comment on them as possible and confining myself to bare facts.

At the outset of the War, when Serbia was the only Balkan country engaged in it, we desired that the War should not spread in the Near East. We did not seek then to bring any other country into it, lest by bringing any one country on our side we should precipitate conflict with another, and unnecessarily and to no good purpose enlarge the area of the War. Therefore, in common with our Allies, on the outbreak of War we assured Turkey that if she would remain neutral, we, the Allies, would see that in the terms of peace Turkey and Turkish territory should not suffer. This situation, of course, was completely changed by the entry of Turkey into the War. For some time, indeed, Turkey resisted German pressure; but when Turkish ships were forced by German officers to fire upon Russian ports and shipping without notice or provocation, war, of course, ensued, and all obligations on the part of the Allies towards Turkey came to an end. That was the first change in the situation.

We—and when I say "we" I mean the-Allies—we and our Allies then concentrated on working for Balkan agreement. This could be secured only by the satisfaction of the reasonable hopes and aspirations of all the Balkan States, including Bulgaria. The mutual concessions necessary to secure such an agreement were things that required mutual consent, and we used all our influence to secure this consent to them. Unfortunately, owing to past circumstances, the feeling between Balkan States was one not of union, but of acute division, and the policy of encouraging division and embittering existing antipathies between them was infinitely easier than the policy of reconciling them and securing union. In my opinion, it is clear that nothing but a decided and preponderating advantage to the Allies in the course of the military events in Europe during the last few months would have enabled us to make the policy of Balkan agreement prevail over the opposite policy of bringing about Balkan war. It is the latter policy that the Sovereigns and Governments of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria—the Sovereigns and Governments—have succeeded in carrying into effect. We were given to understand that in order to secure Balkan union there were certain concessions that Bulgaria would require, especially in Thrace and Macedonia. The Allies were ready to do all in their power to secure these things for Bulgaria; but to obtain the consent of Serbia and Greece to the necessary concessions, it was an essential preliminary that Bulgaria should take the side of the Allies against Turkey. In other words, if Bulgaria was to realise her hopes and aspirations, she must co-operate in the common cause in which were engaged the hopes and aspirations of other neighbouring States, who were to make concessions to her. I need not enter in detail into what those hopes and aspirations on each side were; it will be enough to say that what we describe as reasonable hopes and aspirations were in the main founded upon an opportunity to peoples of the same race, the same sentiments, and the same religion, to join themselves to that State and under that Government which was most akin to them.

We were given to understand, in the course of negotiations, that, except as regards Thrace, the Central Powers—Germany and Austria-Hungary—offered more to Bulgaria as the price of her neutrality than the Allies promised, or could in common fairness promise, to others on condition of Bulgaria's joining with them. I have seen it stated lately that no secret treaty exists between Bulgaria and the Central Powers. I do not know whether it is intended to mean that no agreement, no promise, no condition exists between the Central Powers and Bulgaria. It is asking a little too much to ask us to believe that Bulgaria, who had had large promises from the Central Powers for her neutrality, has been induced to enter into the War without any promises at all. These promises, whatever they are, must be given to her by the Central Powers at the expense of her neighbours, without, of course, any corresponding advantage to those neighbours. Throughout all this we have remained in the most friendly relations with Roumania, who has been entirely favourable to the policy of promoting agreement between her neighbours in the Balkans, and has throughout, according to our information, in all her dealings with them, shown a readiness to promote the same policy we were pursuing, which was that of Balkan agreement, and not Balkan division. The Allies themselves, in constant discussion, have remained united in their diplomatic efforts.

4.0 P.M.

I now come to the question of the moment—the critical question—that of the acute struggle in which Serbia is engaged. Before the War we had no previous alliance or engagement with Serbia, but throughout the War we have naturally, in common with our Allies, given her all the assistance in our power as an Ally. The geographical position of Serbia and the use of our Forces elsewhere has necessarily made that assistance limited, but all that could be given since the outbreak of War has been given freely and unconditionally by the Allies to Serbia. Last winter, it will be within the recollection of everybody, there was an acute crisis in the military position of Serbia. She had to evacuate Belgrade and retire on her own territory before superior forces. It was impossible for her then to receive any assistance by the despatch of troops from outside. The skill and courage with which she turned on her enemies and drove them out of her country is one of the most outstanding and remarkable things that has so far happened in the War. Again, a crisis is upon Serbia, which she is meeting with the same splendid courage as before. But this time the entry of Bulgaria into the War against Serbia makes a great difference in the situation. The attack upon Serbia by Bulgaria raises the question of Treaty obligations between Greece and Serbia. For the attitude and intentions of the Greek Government at the moment, and the feeling of the Greek people, I can only refer to the speeches of Mons. Zaimis and Mons. Venizelos which have recently been published in the Press. But it must be obvious to everyone that the interest of Greece and Serbia is now one, and that in the long run they stand or fall together. It is through Greek territory alone that direct assistance can be given rapidly by the Allies to Serbia. Such help as was within their power to give at once the Allies desired to give to Greece and Serbia in this way, and they accordingly sent such French and British troops as were immediately available to Salonica.

Greece had ordered mobilisation in consequence of the Bulgarian mobilisation. She made a formal protest when the first Allied troops arrived, but that the assistance given in this way is welcome is sufficiently proved by the circumstances of the landing, the reception of the troops, and the facilities for continuing disembarkation which have been given. Indeed, in view of the Treaty between Greece and Serbia, how could there be any other attitude on the part of Greece towards the assistance offered, through her, to Serbia to meet the attack by Bulgaria? In the steps thus taken we have acted in close cooperation with France. The co-operation of Russian troops is promised as soon as they can be made available. The military measures which are best adapted to meet the requirements of the new situation in the Near East are the subject of continuous attention by the military authorities of the Allies, and will be taken in closest consultation with each other. It is not in my province, and if it were it would not be expedient, to make any public disclosure of military plans. I will only say that they will, we believe, be based on principles of sound strategy. Serbia is fighting for her national existence. With her the struggle just now is intense and acute. But all of us are fighting the same issue for ourselves. As the struggle is one, so the issue is one in whatever theatre of war it is taking place. It is a fight for the right to live—not under the shadow of Prussian militarism, that will not observe the ordinary rules of humanity in war, nor in peace leave us free from menace and oppression.