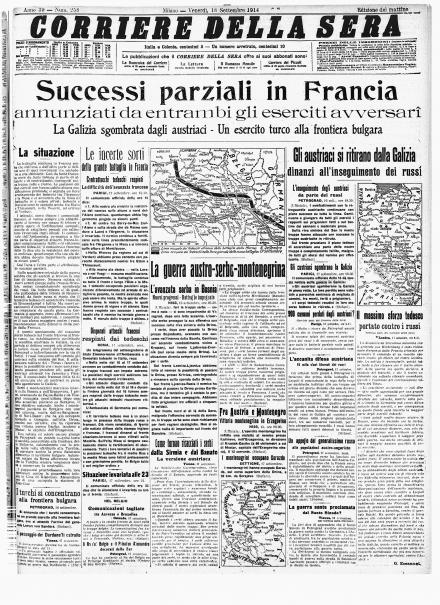

Botta e risposta tra Londra e Berlino

I combattimenti più intensi si concentrano nei pressi di Noyon, nel settore nord-ovest del fronte occidentale; a sud-est, nella regione di Verdun, inizia la battaglia di Woëvre. In mezzo c’è Reims, dove il 18 settembre si vive il secondo giorno consecutivo di bombardamenti. La città vacilla, vibra, scossa dalle esplosioni. Difficile immaginare cosa debbano sopportare gli abitanti. Sentono la paura, certo, ma non può essere solo un’emozione. No, c’è qualcosa di più fisico; c’è il frastuono, si respira polvere, il terreno trema sotto i piedi. E poi c’è quello che si vede; quello che non si vorrebbe mai vedere.

Sul fronte orientale continua l’avanzata russa in Galizia: Sandomierz capitola e Jaroslaw viene data in pasto alle fiamme.

Tra Londra e Berlino si ravviva il vivace botta e risposta di accuse reciproche; diplomazia poca. Ha iniziato Asquith, Primo Ministro inglese. In un discorso pieno di retorica ha puntato il dito contro la Germania: è lei ad aver provocato il conflitto. Austria-Ungheria non pervenuta.

La risposta del Cancelliere tedesco Bethmann-Hollweg si è fatta attendere una decina di giorni. Sulla retorica vince Berlino, Bethmann-Hollweg raggiunge livelli notevolissimi. Per lui la colpa è inglese: Londra avrebbe architettato tutto, manovrando russi e francesi come marionette. E la storia della neutralità belga sarebbe stata solo un pretesto. Fin qui è un punto di vista, comunque opinabile. Ma il Cancelliere fa il passo più lungo della gamba, si “vanta” di aver rispettato la neutralità olandese e svizzera.

Troppo facile. Il Ministero degli esteri britannico pubblica una nota ufficiale: «Il Cancelliere ha scusato la violazione della neutralità belga con le necessità militari, mentre si fa un merito di aver rispettato la neutralità dell’Olanda e della Svizzera. Tale virtù, praticata soltanto in mancanza di un particolare interesse, non sembra un fatto di cui vantarsi molto».

Colpito e affondato.

Davide Sartori

GLI AVVENIMENTI

Politica e società

- Inghilterra: proroga del Parlamento. Discorso di Re Giorgio V.

- Discorso del Primo Ministro inglese Asquith a Edimburgo.

- La Turchia risponde alle proteste e conferma l'abolizione delle capitolazioni, pur rimandandone l’entrata in vigore al 1° novembre.

Fronte occidentale

- Aisne: duri combattimenti attorno Noyon. I tedeschi bombardano ancora Reims.

- Inizia la battaglia della Woëvre.

Fronte orientale

- Polonia: i russi conquistano Sandomierz, attaccano e incendiano Jaroslaw.

Fronte asiatico ed egiziano

- Nella notte 2.000 turchi, con provvigioni, passano da Gaza, seguendo la costa verso la frontiera egiziana.

Fronte d’oltremare

- Sud-ovest dell’Africa: i britannici occupano Luderitz Bay, che i tedeschi avevano evacuato militarmente il 10 agosto.

Parole d'epoca

Official British War Correspondent E. D. Swinton

The Battle of the Aisne - 'Eye Witness' Reports

General Headquarters,

September 18, 1914.

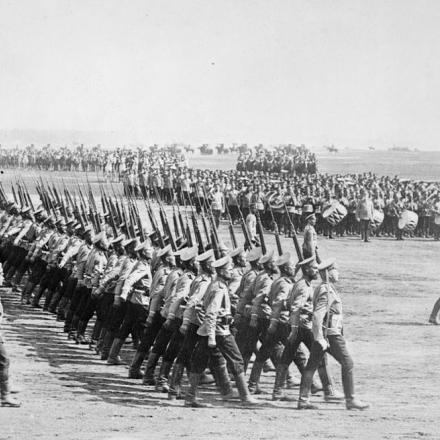

September 14th, the Germans were making a determined resistance along the River Aisne. Opposition, which it was at first thought might possibly be of a rearguard nature, not entailing material delay to our progress, developed and proved to be more serious than was anticipated.

The action, now being fought by the Germans along their line, may, it is true, have been undertaken in order to gain time for some strategic operation or move, and may not be their main stand. But, if this is so, the fighting is naturally on a scale which as to extent of ground covered and duration of resistance, makes it undistinguishable in its progress from what is known as a "pitched battle," though the enemy certainly showed signs of considerable disorganization during the earlier days of their retirement phase.

Whether it was originally intended by them to defend the position they took up as strenuously as they have done, or whether the delay, gained for them during the 12th and 13th by their artillery, has enabled them to develop their resistance and force their line to an extent not originally contemplated cannot be said.

So far as we are concerned the action still being contested is the battle of the Aisne. The foe we are fighting is just across the river along the whole of our front to the east and west. The struggle is not confined to the valley of that river, though it will probably bear its name.

The progress of our operations and the French armies nearest us for the 14th, 15th, 16th, and 17th will now be described.

On Monday, the 14th, those of our troops which had on the previous day crossed the Aisne, after driving in the German rear guards on that evening, found portions of the enemy's forces in prepared defensive positions on the right bank and could do little more than secure a footing north of the river. This, however, they maintained in spite of two counter-attacks delivered at dusk and 10 p.m., in which the fighting was severe.

During the 14th, strong re-enforcements of our troops were passed to the north bank, the troops crossing by ferry, by pontoon bridges, and by the remains of permanent bridges. Close cooperation with the French forces was maintained and the general progress made was good, although the opposition was vigorous and the state of the roads, after the heavy rains, made movements slow. One division alone failed to secure the ground it expected to.

The First Army Corps, after repulsing repeated attacks, captured 600 prisoners and twelve guns. The cavalry also took a number of prisoners. Many of the Germans taken belong to the reserve and Landwehr formations, which fact appears to indicate that the enemy is compelled to draw on other classes of soldiers to fill the gaps in his ranks.

There was a heavy rain throughout the night of September 14th-15th, and during the 15th. The situation of the British forces underwent no essential change. But it became more and more evident that the defensive preparations made by the enemy were more extensive than was at first apparent.

In order to counterbalance these, measures were taken by us to economize our troops and to secure protection from the hostile artillery fire, which was very fierce; and our men continued to improve their own entrenchments. The Germans bombarded our lines nearly all day, using heavy guns, brought, no doubt, from before Maubeuge, as well as those with the corps.

All their counter-attacks, however, failed, although in some places they were repeated six times. One made on the Fourth Guard Brigade was repulsed with heavy slaughter.

An attempt to advance slightly, made by part of our line, was unsuccessful as regards gain of ground, but led to the withdrawal of part of the enemy's infantry and artillery. Further counter-attacks made during the night were beaten off. Rain came on toward evening and continued intermittently until 9 a.m. on the 16th. Besides adding to the discomfort of the soldiers holding the line, the wet weather to some extent hampered the motor transport service, which was also hindered by broken bridges.

On Wednesday, the 16th, there was little change in the situation opposite the British. The efforts made by the enemy were less active than on the previous day, although their bombardment continued throughout the morning and evening. Our artillery fire drove the defenders off one of the salients of their position, but they returned in the evening. Forty prisoners were taken by the Third Division.

On Thursday, the 17th, the situation still remained unchanged in its essentials. The German heavy artillery fire was more active than on the previous day. The only infantry attacks made by the enemy were on the extreme right of our position, and, as had happened before, were repulsed with heavy loss, chiefly, on this occasion, by our field artillery.

In order to convey some idea of the nature of the fighting it may be said that along the greater part of our front the Germans have been driven back from the forward slopes on the north of the river. Their infantry are holding strong lines of trenches among and along the edge of the numerous woods which crown the slopes. These trenches are elaborately constructed and cleverly concealed. In many places there are wire entanglements and lengths of rabbit fencing.

Both woods and open are carefully aligned, so that they can be swept by rifle fire and machine guns, which are invisible from our side of the valley. The ground in front of the infantry trenches is also, as a rule, under crossfire from the field artillery placed on neighbouring features and under high-angle fire from pieces placed well back behind the woods on top of the plateau.

A feature of this action, as of the previous fighting, is the use by the enemy of their numerous heavy howitzers, with which they are able to direct long-range fire all over the valley and right across it. Upon these they evidently place great reliance.

Where our men are holding the forked edges of the high ground on the north side they are now, strongly entrenched. They are well fed, and in spite of the wet weather of the last week are cheerful and confident.

The bombardment by both sides has been very heavy, and on Sunday, Monday and Tuesday was practically continuous. Nevertheless, in spite of the general din caused by the reports of the immense number of heavy guns in action along our front on Wednesday, the arrival of the French force acting against the German right flank was at once announced on the east of our front, some miles away, by the continuous roar of their quick-firing artillery, with which their attack was opened.

So far as the British are concerned, the greater part of this week has been passed in bombardment, in gaining ground by degrees, and in beating back severe counter-attacks with heavy slaughter. Our casualties have been severe, but it is probable that those of the enemy are heavier.

The rain has caused a great drop in the temperature, and there is more than a distinct feeling of autumn in the air, especially in the early mornings.

On our right and left the French have been fighting fiercely and have also been gradually gaining ground. One village has already during this battle been captured and recaptured twice by each side, and at the time of writing remains in the hands of the Germans.

The fighting has been at close quarters and of the most desperate nature, and the streets of the village are filled with dead on both sides.

The Germans are a formidable enemy, well trained, long prepared, and brave. Their soldiers are carrying on the contest with skill and valour. Nevertheless they are fighting to win anyhow, regardless of all the rules of fair play, and there is evidence that they do not hesitate at anything in order to gain victory.

A large number of the tales of their misbehaviours are exaggeration and some of the stringent precautions they have taken to guard themselves against the inhabitants of the areas traversed are possibly justifiable measures of War. But, at the same time, it has been definitely established that they have committed atrocities on many occasions.

Among the minor happenings of interest is the following: During a counter-attack by the German Fifty-third Regiment on positions of the Northampton and Queen's Regiments on Thursday, the 17th, a force of some 400 of the enemy were allowed to approach right up to the trench occupied by a platoon of the former regiment, owing to the fact that they had held up their hands and made gestures that were interpreted as signs that they wished to surrender.

When they were actually on the parapet of the trench held by the Northamptons they opened fire on our men at point-blank range.

Unluckily for the enemy, however, flanking them and only some 400 yards away, there happened to be a machine gun manned by a detachment of the Queen's. This at once opened fire, cutting a lane through their mass, and they fell back to their own trench with great loss. Shortly afterward they were driven further back, with additional loss, by a battalion of Guards which came up in support.

The enemy is still maintaining himself along the whole front, and, in order to do so, is throwing into the fight detachments composed of units from different formations, the active army, reserve, and Landwehr, as is shown by the uniforms of the prisoners recently captured.

Our progress, although slow on account of the strength of the defensive positions against which we are pressing, has in certain directions been continuous; but the present battle may well last for some days more before a decision is reached, since it now approximates somewhat to siege warfare.

The Germans are making use of searchlights. This fact, coupled with their great strength in heavy artillery, leads to the supposition that they are employing material which may have been collected for the siege of Paris.

A buried store of the enemy's munitions of war was also found, not far from the Aisne, ten wagon loads of live shell and two wagon loads of cable being dug tip. Traces here discovered of large quantities of stores having been burned- a ll tending to show that as far back as the Aisne the German retirement was hurried.

On Sunday, the 10th, nothing of importance occurred until the afternoon, when there was a break in the clouds and an interval of feeble sunshine, which was hardly powerful enough to warm the soaking troops. The Germans took advantage of this brief spell of fine weather to make several counter-attacks against different points. These were all repulsed with loss to the enemy, but the casualties incurred by us were by no means light.

The offensive against one or two points was renewed at dusk, with no greater success. The brunt of the resistance has naturally fallen upon the infantry. In spite of the fact that they have been drenched to the skin for some days and their trenches have been deep in mud and water, and in spite of the incessant night alarms and the almost continuous bombardment to which they have been subjected, they have on every occasion been ready for the enemy's infantry when the latter attempted to assault, and they have beaten them back with great loss.

Parole d'epoca

Declaration by authors - a righteous war

The Times del 18 settembre 1914

We have received the following statement:

The undersigned writers, comprising amongst them men and women of the most divergent political and social views, some of them having been for years ardent champions of good will towards Germany, and many of the extreme advocates of peace, are nevertheless agreed that Great Britain could not without dishonour have refused to take part in the present war.

No one can read the full diplomatic correspondence published in the White Paper without seeing that the British representatives were throughout labouring whole-heartedly to preserve the peace of Europe, and that their conciliatory efforts were cordially received by both France and Russia.

When these efforts failed, Great Britain had still not direct quarrel with any Power.

She was eventually compelled to take up arms because, together with France, Germany and Austria, she had solemnly pledged herself to maintain the neutrality of Belgium. As soon as danger to that neutrality arose she questions both France and Germany as to their intentions. France immediately renewed her pledge not to violate Belgian neutrality; Germany refused to answer, and soon made all answer needless by her actions. Without even the pretence of a grievance against Belgium, she made war on the weak and unoffending country she had undertaken to protect, and has since carried out her invasion with a calculated and ingenious ferocity which has raised questions other and no less grave than that of the wilful disregard of treaties.

When Belgium in her dire need appealed to Great Britain to carry out her pledge this country’s course was clear. She had either to break faith, letting the sanctity of treaties and the rights of small nations count for nothing before the threat of naked force, or she had to fight. She did not hesitate, and we trust she will not lay down arms till Belgium’s integrity is restored and her wrongs redressed.

The treaty with Belgium made our duty clear, but many of us feel that, even if Belgium had not been involved, it would have been impossible for Great Britain to stand aside while France was dragged into war and destroyed. To permit the ruin of France would be a crime against liberty and civilization. Even those of us who question the wisdom of a policy of Continental Ententes or Alliances refuse to see France struck down by a foul blow dealt in violation of a treaty.

We observe that various German apologists, official and semi-official, admit that their country has been false to its pledged word, and dwell almost with pride on the “frightfulness” of the examples by which is has sought to spread terror in Belgium, but they excuse all these proceedings by a strange and novel plea. German culture and civilization are so superior to those of other nations that all steps taken to assert them are more than justified; and the destiny of Germany to be the dominating force in Europe and the world is so manifest that ordinary rules of morality do not hold in her case, but actions are good or bad simply as they help or hinder the accomplishment of that destiny.

These views, inculcated upon the present generation of Germans by many celebrated historians and teachers, seem to us both dangerous and insane. Many of us have dear friends in Germany, many of us regard German culture with the highest respect and gratitude; but we cannot admit that any nation has the right by brute force to impose its culture upon other nations, nor that the iron military bureaucracy of Prussia represents a higher form of human society than the free constitutions of Western Europe.

Whatever the world-destiny of Germany may be, we in Great Britain are ourselves conscious of a destiny and duty. That destiny and duty, alike for us and for all the English-speaking race, call upon us to uphold the rule of the common justice between civilized peoples, to defend the rights of small nations, and to maintain the free and law-abiding ideals of Western Europe against the rule of “Blood and Iron” and the domination of the whole Continent by the military caste.

For these reasons and others the undersigned feel bound to support the cause of the Allies with all their strength, with a full conviction of its righteousness, and with a deep sense of its vital import to the future of the world.

William Archer

H. Granville Barker

J. M. Barrie

Arnold Bennett

A. C. Benson

Robert Hugh Benson

Laurence Binyon

Robert Bridges (the Poet Laureate)

Hall Caine

R. C. Carton

C. Haddon Chambers

G. K. Chesterton

Hubert Henry Davies

Arthur Conan Doyle

John Galsworthy

F. Anstey

H. Rider Haggard

Thomas Hardy

Anthony H. Hawkins

Maurice Hewlett

Robert Hichens

Jerome K. Jerome

Henry Arthur Jones

Rudyard Kipling

W. J. Locke

John Masefield

A. E. W. Mason

Henry Newbolt

Barry Pain

Gilbert Parker

Eden Phillpotts

Arthur Pinero

Arthur Quiller-Couch

Owen Seaman

May Sinclair

Flora Annie Steel

George M. Trevelyan

George Otto Trevelyan

H. G. Wells

Israel Zangwill

September, 1914.

Parole d'epoca

Sottotenente Charles Caldwell Sills

Diario

At dawn the firing starts again, and this time we have to stay in our trenches the whole day long. I wonder how many thousands of shrapnel bullets must have been fired at us during the last 24 hours. It is a wearing, trying job and gets on one's nerves fearfully.

We manage at daybreak to send out a search party to bring in any wounded that there may be out in front and we find some will have been a three days, wounded, with no water, no food and have shelter.

And when found a large number say they are not half as bad as someone else close to them and will we look at the others first. Magnificent spirit, and people who say England is going to the dogs and that the men of England at the present day are inferior to those of the past do not know what they are talking about.

The rain comes down at about 9am and falls all day long in sheets.

All the trenches of full of water. No draining any good. A cold wind on top of the hill does not improve matters. But again everyone tries to be as cheery as possible and so night comes on. The battle stops for a bit and again we have some rest. But little sleep, it is too cold really for that.

At dawn, firing starts again. How long can it go on, I wonder, and how long can one's nerves stand it. Of course, one is safe enough as far as things go in trenches with cover, etc, but it is the noise and shock that tires one.

A whistle and a bang, and the noise that sounds like a shower of hail as the shrapnel comes through the branches of the trees, and in all is over for a minute and then at it again.