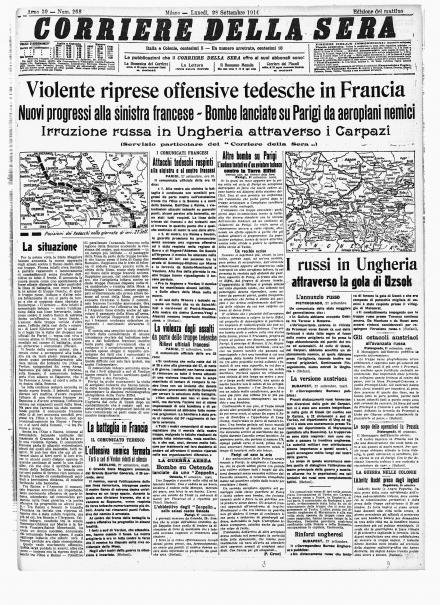

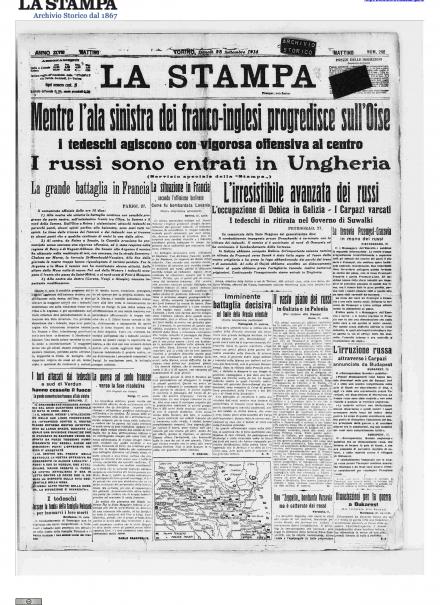

Sull'Aisne tutto in stallo

Vienna non cambia, non all’apparenza almeno. Sarà per l’ottimismo dei giornali, ma la vita tenta di proseguire sui binari della normalità: i tanti Cafè sono sempre affollati, nessuno vuole farsi condizionare dalle ristrettezze.

Certo, in alcuni ambienti l’umore sembra rispecchiare il meteo: pessimo, cielo plumbeo e pioggia battente da una decina di giorni. Ma c’è chi vede un lato positivo anche in questo. La regione dell’Impero più soggetta ad alluvioni è proprio la Galizia; chissà, potrebbe essere il cielo a fermare i russi.

No, non per ora. Le armate zariste stringono ancor di più le mani al collo di Przemysl e avanzano in Ungheria.

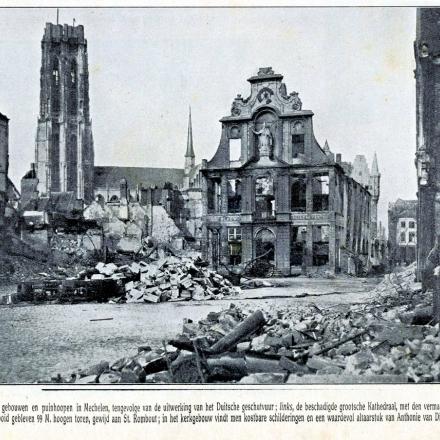

Sul fronte occidentale la battaglia dell’Aisne si conclude in stallo, pari e patta; le attenzioni sono tutte per la corsa al mare. La situazione si aggrava in Belgio: i tedeschi sono stanchi della strenua resistenza locale. Conquistata Mechelen, il 28 settembre inizia l’assedio di Anversa: le due cinture fortificate più esterne hanno ceduto, ma per le truppe tedesche resta ancora tanto sudore da spendere.

Ad allungare la lista di danni collaterali ci sono alcune imbarcazioni italiane, affondate nell’Adriatico da mine austro-ungariche. Sull’orizzonte viennese appare l’ombra dell’ennesima crisi diplomatica.

Davide Sartori

GLI AVVENIMENTI

Politica e società

- In Italia il Governo ammonisce severamente i cittadini italiani in procinto di arruolarsi negli eserciti degli Stati belligeranti, minacciandoli di gravi pene e della perdita della cittadinanza.

- Per la prima volta gli aerei tedeschi mostrano insegne distintive che li differenziano dagli altri.

- Il Generale Sir A. Barrett viene nominato Comandante dell’Indian Expeditionary Force "D" per la Mesopotamia.

Fronte occidentale

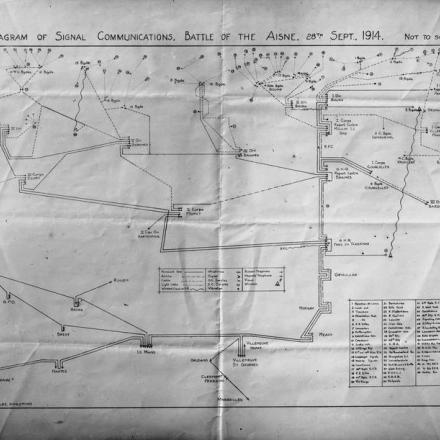

- La prima battaglia dell'Aisne si conclude con una situazione di stallo; ma sul fronte occidentale continua la “corsa al mare”.

- Infuria la battaglia di Albert.

- In Belgio inizia l’assedio di Anversa. Dopo la caduta di due cinture fortificate che circondano la città, le truppe tedesche iniziano l'attacco al nucleo urbano. Bombardamento dei forti Waelhem, Wavre, St. Catherine.

- Completata l'occupazione tedesca di Mechelen.

Fronte orientale

- La cavalleria russa entra in Ungheria.

- Polonia: i russi si impossessano di Krosno e del passo Dukla.

- I russi iniziano l'assedio di Przemysl.

Fronte meridionale

- Alcune paranze italiane in Adriatico saltano in aria per scoppio di mine. Dieci le vittime.

- Truppe greche e bande epirote occupano Berat in Albania.

Parole d'epoca

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Siege of Antwerp

It was at this period that a great change came over both the object and the locality of the operations.

This change depended upon two events which occurred far to the north, and reacted upon the great armies locked in the long grapple of the Aisne. The first of these controlling circumstances was that, by the movement of the old troops and the addition of new ones, each army had sought to turn the flank of the ether in the north, until the whole centre of gravity of the war was transferred to that region.

A new French army under General Castelnau, whose fine defence of Nancy had put him in the front of French leaders, had appeared on the extreme left wing of the Allies, only to be countered by fresh bodies of Germans, until the ever-extending line lengthened out to the manufacturing districts of Lens and Lille, where amid pit-shafts and slag-heaps the cavalry of the French and the Germans tried desperately to get round each other's flank.

The other factor was the fall of Antwerp, which released very large bodies of Germans, who were flooding over western Belgium, and, with the help of great new levies from Germany, carrying the war to the sand-dunes of the coast. The operations which brought about this great change open up a new chapter in the history of the war.

The Belgians, after the evacuation of Brussels in August, had withdrawn their army into the widespread fortress of Antwerp, from which they made frequent sallies upon the Germans who were garrisoning their country.

Great activity was shown and several small successes were gained, which had the useful effect of detaining two corps which might have been employed upon the Aisne. Eventually, towards the end of September, the Germans turned their attention seriously to the reduction of the city, with a well-founded confidence that no modern forts could resist the impact of their enormous artillery.

They drove the garrison within the lines, and early in October opened a bombardment upon the outer forts with such results that it was evidently only a matter of days before they would fall and the fine old city be faced with the alternative of surrender or destruction.

The Spanish fury of Parma's pikemen would be a small thing compared to the furor Teutonicusworking its evil deliberate will upon town-hall or cathedral, with the aid of fire-disc, petrol-spray, or other products of Kultur.

The main problem before the Allies, if the town could not be saved, was to insure that the Belgian army should be extricated and that nothing of military value which could be destroyed should be left to the invaders.

No troops were available for a rescue for the French and British old formations were already engaged, while the new ones were not yet ready for action. In these circumstances, a resolution was come to by the British leaders which was bold to the verge of rashness and so chivalrous as to be almost quixotic.

It was determined to send out at the shortest notice a naval division, one brigade of which consisted of marines, troops who are second to none in the country's service, while the other two brigades were young amateur sailor volunteers, most of whom had only been under arms for a few weeks.

It was an extraordinary experiment, as testing how far the average sport-loving, healthy-minded young Briton needs only his equipment to turn him into a soldier who, in spite of all rawness and inefficiency, can still affect the course of a campaign.

This strange force, one-third veterans and two-thirds practically civilians, was hurried across to do what it could for the failing town, and to demonstrate to Belgium how real was the sympathy which prompted us to send all that we had.

A re-enforcement of a very different quality was dispatched a few days later in the shape of the Seventh Division of the Regular Army, with the Third Division of Cavalry. These fine troops were too late, however, to save the city, and soon found themselves in a position where it needed all their hardihood to save themselves.

The Marine Brigade of the Naval Division under General Paris was dispatched from England in the early morning and reached Antwerp during the night of October 3rd. They were about 2,000 in number. Early next morning they were out in the trenches, relieving some weary Belgians. The Germans were already within the outer enceinte and drawing close to the inner.

For forty-eight hours they held the line in the face of heavy shelling. The cover was good and the losses were not heavy. At the end of that time the Belgian troops, who had been a good deal worn by their heroic exertions, were unable to sustain the German pressure, and evacuated the trenches on the flank of the British line. The brigade then fell back to a reserve position in front of the town.

On the night of the 5th the two other brigades of the division, numbering some 5,000 amateur sailors, arrived in Antwerp, and the whole force assembled on the new line of defence. Mr. Winston Churchill showed his gallantry as a man, and his indiscretion as a high official, whose life was of great value to his country by accompanying the force from England.

The bombardment was now very heavy, and the town was on fire in several places. The equipment of the British left much to be desired, and their trenches were as indifferent as their training. Nonetheless they played the man and lived up to the traditions of that great service upon whose threshold they stood.

For three days these men, who a few weeks before had been anything from schoolmasters to tram-conductors, held their perilous post. They were very raw, but they possessed a great asset in their officers, who were usually men of long service. But neither the lads of the naval brigades nor the war-worn and much-enduring Belgians could stop the mouths of those inexorable guns.

On the 8th it was clear that the forts could no longer be held. The British task had been to maintain the trenches which connected the forts with each other, but if the forts went it was clear that the trenches must be outflanked and untenable. The situation, therefore, was hopeless, and all that remained was to save the garrison and leave as little as possible for the victors.

Some thirty or forty German merchant ships in the harbour were sunk and the great petrol tanks were set on fire. By the light of the flames the Belgians and British forces made their way successfully out of the town, and the good service rendered later by our Allies upon the Yser and elsewhere is the best justification of the policy which made us strain every nerve in order to do everything which could have a moral or material effect upon them in their darkest hour.

Had the British been able to get away unscathed, the whole operation might have been reviewed with equanimity if not with satisfaction, but, unhappily, a grave misfortune, arising rather from bad luck than from the opposition of the enemy, came upon the retreating brigades, so that very many of our young sailors after their one week of crowded life came to the end of their active service for the war.

On leaving Antwerp it had been necessary to strike to the north in order to avoid a large detachment of the enemy who were said to, be upon the line of the retreat. The boundary between Holland and Belgium is at this point very intricate, with no clear line of demarcation, and a long column of British somnambulists, staggering along in the dark after so many days in which they had for the most part never enjoyed two consecutive hours of sleep, wandered over the fatal line and found themselves in firm but kindly Dutch custody for the rest of the war.

Parole d'epoca

Colonnello Ernest D. Swinton, DSO

Trench Warfare Begins on the Aisne

September 14th, the Germans were making a determined resistance along the River Aisne . Opposition, which it was at first thought might possibly be of a rear-guard nature, not entailing material delay to our progress, developed and proved to be more serious than was anticipated.

The action, now being fought by the Germans along their line, may, it is true, have been undertaken in order to gain time for some strategic operation or move, and may not be their main stand. But, if this is so, the fighting is naturally on a scale which as to extent of ground covered and duration of resistance, makes it undistinguishable in its progress from what is known as a "pitched battle," though the enemy certainly showed signs of considerable disorganization during the earlier days of their retirement phase.

Whether it was originally intended by them to defend the position they took up as strenuously a they have done, or whether the delay, gained for them during the 12th and 13th by their artillery, has enabled them to develop their resistance and force their line to an extent not originally contemplated cannot be said.

So far as we are concerned the action still being contested is the Battle of the Aisne. The foe we are fighting is just across the river along the whole of our front to the east and west. The struggle is not confined to the valley of that river, though it will probably bear it name.

The progress of our operations and the French armies nearest us for the 14th, 15th, 16th, and 17th will now be described:

On Monday, the 14th, those of our troops which had on the previous day crossed the Aisne, after driving in the German rear guards on that evening, found portions of the enemy's forces in prepared defensive positions on the right bank and could do little more than secure a footing north of the river. This, however, they maintained in spite of two counter-attacks delivered at dusk and 10 p. m., in which the fighting was severe.

During the 14th, strong re-enforcements of our troops were passed to the north bank, the troops crossing by ferry, by pontoon bridges, and by the remains of permanent bridges. Close cooperation with the French forces was maintained and the general progress made was good, although the opposition was vigorous and the state of the roads, after the heavy rains, made movements slow. One division alone failed to secure the ground it expected to.

The First Army Corps, after repulsing repeated attacks, captured 600 prisoners and twelve guns. The cavalry also took a number of prisoners. Many of the Germans taken belong to the reserve and Landwehr formations, which fact appears to indicate that the enemy is compelled to draw on other classes of soldiers to fill the gaps in his ranks.

There was a heavy rain throughout the night of September 14th-15th, and during the 15th. The situation of the British forces underwent no essential change. But it became more and more evident that the defensive preparations made by the enemy were more extensive than was at first apparent.

In order to counterbalance these, measures were taken by us to economize our troops and to secure protection from the hostile artillery fire, which was very fierce; and our men continued to improve their own intrenchments. The Germans bombarded our lines nearly all day, using heavy guns, brought, no doubt, from before Maubeuge, as well as those with the corps.

All their counter attacks, however, failed, although in some places they were repeated six times. One made on the Fourth Guard Brigade was repulsed with heavy slaughter.

An attempt to advance slightly, made by part of our line, was unsuccessful as regards gain of ground, but led to the withdrawal of part of the enemy's infantry and artillery.

Further counter-attacks made during the night were beaten off. Rain came on toward evening and continued intermittently until 9 a.m. on the 16th. Besides adding to the discomfort of the soldiers holding the line, the wet weather to some extent hampered the motor transport service, which was also hindered by broken bridges.

On Wednesday, the 16th, there was little change in the situation opposite the British. The efforts made by the enemy were less active than on the previous day, although their bombardment continued throughout the morning and evening. Our artillery fire drove the defenders of one of the salients of their position but they returned in the evening. Forty prisoners were taken by the Third Division.

On Thursday, the 17th, the situation still remained unchanged in its essential. The German heavy artillery fire was more active than on the previous day, The only infantry attacks made by the enemy were on the extreme right of our position, and, as had happened before, were repulsed with heavy loss, chiefly, on this occasion, by our field artillery.

In order to convey some idea of the nature of the fighting it may be said that long the greater part of our front the Germans have been driven back from the forward slopes on the north of the river. Their infantry are holding strong lines of trenches among and along the edge of the numerous woods which crown the slopes. These trenches are elaborately constructed and cleverly concealed. In many places there are wire entanglements and length of rabbit fencing.

Both woods and open are carefully aligned, so that they can be swept by rifle fire and machine guns, which are invisible from our side of the valley. The ground in front of the infantry trenches is also, as a rule, under crossfire from the field artillery placed on neighboring features and under high-angle fire from pieces placed well back behind the woods on top of the plateau.

A feature of this action, as of the previous fighting, is the use by the enemy of their numerous heavy howitzers, with which they are able to direct long-range fire all over the valley and right across it. Upon these they evidently place great reliance....

So far as the British are concerned, the greater part of this week has been passed in bombardment, in gaining ground by degrees, and in beating back severe counter-attacks with heavy slaughter. Our casualties have been severe, but it is probable that those of the enemy are heavier.

On our right and left the French have been fighting fiercely, and have also been gradually gaining ground. One village has already during this battle been captured and recaptured twice by each side, and at the time of writing remains in the hands of the Germans.

The fighting has been at close quarters and of the most desperate nature, and the streets of the village are filled with dead on both sides.

The Germans are a formidable enemy, well trained, long prepared, and brave. Their soldiers are carrying on the contest with skill and valor. Nevertheless they are fighting to win anyhow, regardless of all the rules of fair play, and there is evidence that they do not hesitate at anything in order to gain victory.

A large number of the tales of their misbehaviors are exaggeration and some of the stringent precautions they have taken to guard themselves against the inhabitants of the areas traversed are possibly justifiable measures of war. But, at the same time, it has been definitely established that they have committed atrocities on many occasions.

Among the minor happenings of interest is the following: During a counter-attack by the German Fifty-third Regiment on positions of the Northampton and Queen's Regiments on Thursday, the 17th, a force of some 400 of the enemy were allowed to approach right up to the trench occupied by a platoon of the former regiment owing to the fact that they had held up their hands and made gestures that were interpreted as signs that they wished to surrender. When they were actually on the parapet of the trench held by the Northamptons they opened fire on our men at point-blank range.

Unluckily for the enemy, however, flanking them and only some 400 yards away, there happened to be a machine gun manned by a detachment of the Queen's. This at once opened fire, cutting a lane through their mass, and they fell back to their own trench with great loss. Shortly afterward they were driven further back, with additional loss, by a battalion of Guards which came up in support.

The following special order has been issued to the troops:

"September 17, 1914.

"Once more I have to express my deep appreciation of the splendid behavior of the officers, non-commissioned officers, and men of the army under my command throughout the great Battle of the Aisne, which has been in progress since the evening of the 12th inst., and the Battle of the Marne, which lasted from the morning of the 6thto the evening of the 10th, and finally ended in the precipitate flight of the enemy.

"When we were brought face to face with a position of extraordinary strength, carefully intrenched and prepared for defense by an army and staff which are thorough adepts in such work, throughout the 13th and 14th, that position was most gallantly attacked by the British forces and the passage of the Aisne effected. This is the third day the troops have been gallantly holding the position they have gained against most desperate counterattacks and the hail of heavy artillery.

"I am unable to find adequate words in which to express the admiration I feel for their magnificent conduct.

"The French armies on our right and left are making good progress, and I feel sure that we have only to hold on with tenacity to the ground we have won for a very short time longer when the Allies will be again in full pursuit of a beaten enemy.

"The self sacrificing devotion and splendid spirit of the British army in France will carry all before it.

"J. D. P. FRENCH, Field Marshal,

"Commander in Chief of the British Army in the Field."

The enemy is still maintaining himself along the whole front, and, in order to do so, is throwing into the fight detachments composed of units from different formations, the active army, reserve, and Landwehr, as is shown by the uniforms of the prisoners recently captured.

Our progress, although slow on account of the strength of the defensive positions against which we are pressing, has in certain directions been continuous; but the present battle may well last for some days more before a decision is reached, since it now approximates somewhat to siege warfare.

The Germans are making use of searchlights. This fact, coupled with their great strength in heavy artillery, leads to the supposition that they are employing material which may have been collected for the siege of Paris.

A buried store of the enemy's munitions of war was also found, not far from the Aisne, ten wagon loads of live shell and two wagon loads of cable being dug up. Traces were discovered of large quantities of stores having been burned --all tending to show that as far back as the Aisne the German retirement was hurried.

On Sunday, the 20th, nothing of importance occurred until the afternoon, when there was a break in the clouds and an interval of feeble sunshine, which was hardly powerful enough to warm the soaking troops. The Germans took advantage of this brief spell of fine weather to make several counter-attacks against different points. These were all repulsed with loss to the enemy, but the casualties incurred by us were by no means light.

The offensive against one or two points was renewed at dusk, with no greater success. The brunt of the resistance has naturally fallen upon the infantry. In spite of the fact that they have been drenched to the skin for some days and their trenches have been deep in mud and water, and in spite of the incessant night alarms and the almost continuous bombardment to which they have been subjected, they have on every occasion been ready for the enemy's infantry when the latter attempted to assault, and they have beaten them back with great loss.

General Headquarters, September 18, 1914