Compensi inesistenti

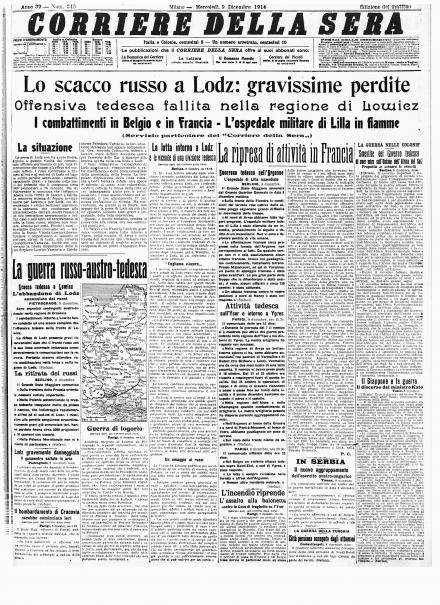

Il 9 dicembre il Governo italiano si appella all’articolo 7 della Triplice Alleanza: da Roma è partita una formale richiesta di compensi; l’interlocutore è l’Impero asburgico. È vero, in caso di conquiste austro-ungariche nei Balcani ci spetterebbe un indennizzo, ma il nostro tempismo fa pensare a uno scherzo: siamo decisamente in ritardo; i serbi hanno vinto a Rudnik, sul Kolubara e hanno riconquistato Valjevo. Le armate asburgiche si ritirano più o meno ovunque, lasciandosi alle spalle tutti i territori occupati. Cosa dovrebbe darci l’Austria-Ungheria?

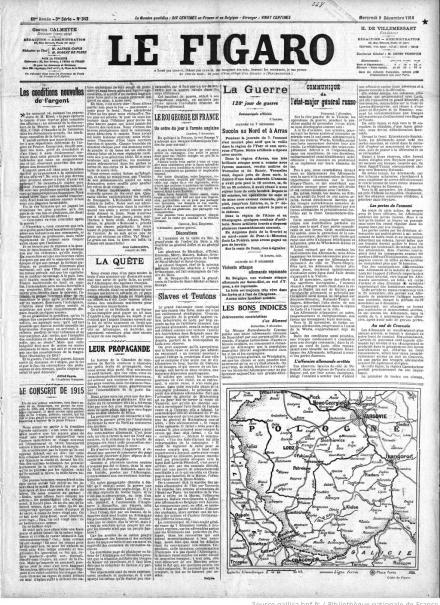

Sul fronte orientale i tedeschi impegnano i russi a Mlawa e Piotrkow. L’idea è sempre la stessa: accerchiare Varsavia da nord e da sud. I combattimenti si fanno più feroci, ripercorrendo gli stessi passi compiuti appena un mese e mezzo prima.

In Mesopotamia i britannici occupano Al-Qurnah: hanno impiegato meno di una settimana per costringere i turchi a evacuare la città, abbandonata al nemico. Anche qui occhio a sottovalutare la presa: Al-Qurnah sorge alla confluenza del Tigri e dell’Eufrate e chi controlla i due grandi fiumi ha in pugno l’intero Iraq.

Davide Sartori

GLI AVVENIMENTI

Politica e società

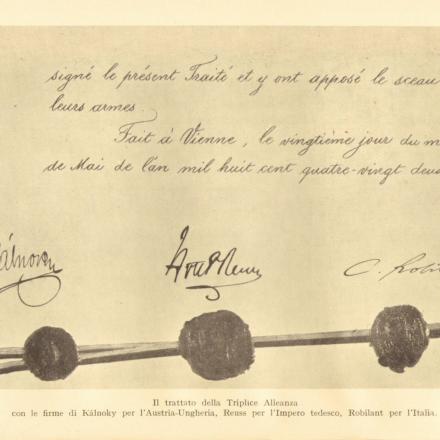

- Il Governo italiano invia al Governo austriaco una richiesta di compensi per le conquiste fatte in Serbia, in base all'art. 7 della Triplice.

- Gran Bretagna: il processo ad Adolph Ahlers per alto tradimento si conclude con una condanna.

Fronte orientale

- Battaglia per Varsavia: pesanti combattimenti attorno Mlawa e Piotrkow.

Fronte meridionale

- I serbi occupano di nuovo Valjevo.

Fronte asiatico ed egiziano

- Al-Qurnah, evacuata dai turchi, viene occupata dalle truppe britanniche.

Parole d'epoca

Sergeant Bernard Joseph Brookes

Diario

We got up next morning rather later than was usual, and this foretold that we were for the trenches that night.

The whole Battalion went to the Baths, and to use a soldier’s expression, "That did it."

Let me explain, and at the same time apologise for mentioning a matter which is very unpleasant, but nevertheless quite true, and an important feature in the discomforts which one has to undergo at the front.

After the bath, the dirty clothes are given in and "clean" washing issued out to all the men.

For a short time all is well. On the march back one gets rather warm and a careful observer will notice a large amount of wriggling and scratching going on, and then the men realise that they are "chatty" or "crumby."

Of course at first it is exceedingly unpleasant and repulsive, but like so many other things, one has to get used to this state, and once started it is almost impossible to get rid of these objectionable livestock. For eight months I was in this state.

After dinner there was plenty for the signallers to do, as we were off to the trenches that night, and by the time I had finished my cycling duty, the Battalion had left. I was rather in a "stew" and made inquiries as to the direction taken and managed, on my cycle, to catch up with my Company about half a mile behind the firing line. I was told that I had to go back, find the dressing station (First Aid Post) leave my cycle there and come to the trenches with the Stretcher Bearers, who knew the way.

On arriving at the Dressing Station I was instructed where to put my cycle, but the Stretcher Bearers had gone, and I was stranded.

Over the wire I was informed that on account of the fever scare I was not to go to a signalling station, but to remain with the company, and that as there was a shortage of men, I was to come down that night.

My directions were as follows:-"Straight up the road until a barrier of two carts is reached, and 50 yards past the barrier there is an opening in the hedge which leads on to a field. By going at right angles with the road, a farm would be sited, and then inquire again."

It was now about 8 PM, and I started with full pack, 250 rounds of ammunition (which weigh very heavily), rifle, blanket (wrapped in my waterproof sheet) slung over my back, and overcoat on, for it was raining; feeling well loaded.

There was a slight fog, and it was pitch black, except that now and again a flare would shine dimly through the mist, dying out, and making the darkness still more intense. I proceeded along the road past Chappelle d'Armentieres, and bumped against the barrier, thereby knowing that I was on the right track.

The bullets were flying around, and being alone, I did not feel quite comfortable. I was very warm, so I halted behind the carts for a rest, during which time, the Durham Light Infantry, who we relieved, came from the trenches, and one or two stragglers told me that one of our officers had been shot going up, and a few seconds later he came along on a stretcher.

This did not make me feel any more comfortable, and I began to wish that I had somebody with me.I pulled myself together, and got on until I came across the opening of which I had been told, and entered.

My first few steps took me knee deep in mud, and being such hard work over the ploughed fields in this condition, I was perspiring freely. I dared not get off the beaten track in case I should miss the farm.

After a distance which seemed terribly long and hard (for every time I heard a rifle shot I "ducked", which made my pack and blanket shift into a most uncomfortable position) at last, through the fog, I spotted the farm. I took shelter behind a wall which had a good share of shell holes, and then I heard some very queer noises proceeding from the other side.

After a few seconds it stopped - was it somebody in pain who had been hit? - And again it started, so I went round to investigate and, joy of joys, I found a soldier filling a rum jar with water from a very old and rusty pump.

I enquired the way to the part of the trenches which were being occupied by the Queen's Westminsters. His reply to the effect that he had never heard of them, rather upset my dignity. I told him that we were relieving the Durham Light Infantry, and he directed me to follow by the side of a communication trench, which was full of water and did not permit of one using it, for five hundred yards; and I would then arrive at my destination.

I found that the communication trench (or rather ditch) which I had been following, broke off in two directions about 50 yards from the farm, but as he said that we were on the right, I followed on what I afterwards discovered was an old front line trench.

However, I did not know this at the time, and continued on my way. I must have gone nearly a mile before I came to the conclusion that something was wrong, and I became desperate. The "whiz" of the bullets told me that I was going parallel with the trenches, so I struck off at right angles across a field, hoping to meet somebody. I had not gone more than 50 yards when I saw a light. My heart beat rapidly, - where was I? Were these the British or German trenches?

I laid down flat in the mud and listened, and heard such language which perhaps at ordinary times might make me blush, but now it was like the sound of sweet music. I went nearer making such remarks as "I say, old chap" very quietly for I did not know where the Germs were, and I was "some windy".

No notice was taken of my remark, for I was outside the trench and no doubt I spoke to softly to be heard. I went nearer and put one foot inside the trench when a gruff voice shouted "who the - - - hell are you?”

I explained that I was in the Queen’s Westminster rifles, but that did not seem to satisfy him as he had never heard the name of our regiment.

After explanations and a chat with an Officer who gave me a tot of rum, I was informed that I would have to go about a mile to the left, and that, as the trenches in parts were full of water, I had better get out again and walk along the top.

Once inside, I did not quite like the idea of being on top again, but as there were some men about, it was not so bad.

The Germs, I was told, were some four or five hundred yards in front. I got out and crossed some fields, being challenged several times, and asking if I was going in the correct direction, when at last I came across my Battalion about 10.30 PM saying a sincere prayer, and heaving a sigh of relief.I had the only "dug-out" left, and it was very badly built, the bottom being under the level of the remainder, the result was about three inches of mud and water.

At that time I did not know the way to construct a good "dug-out" (or "buggy-hutch" as it is called) otherwise I might have built another, although the ground being so wet, and there being no wood available then, as there is now for such purposes, I might not have made a great success of it.

However I got my waterproof sheet on the ground, and was thankful to get my pack, blankets, and equipment off my back.

No sooner had I done this when I was told that I was on ration fatigue and had to go out of the trenches twice again to the farm, and bring in a sack of coke and a tin of tea. By this time I was wet through to the skin, and it was near midnight, and I thought that I would be able to get some rest, but I was deceived for, on my return, I had two hours Guard to do.

At 1.30 am I was detailed to form one of a party to relieve others who were trench digging out in front. A new trench was being made as our present one in places had 6 ft of water in it. So, as soon as I had finished my guard, about 2.00 am, I went about 50 yards in front of our line in the rain and mist to help in the making of a new trench.

I had done some digging in England which permitted an occasional rest, but when digging under fire it is a different tale altogether. In the previous party two men had been hit, and we had to dig deep enough to get into the hole under cover, and then make up the line.

We dug with feverish haste, and were getting on well, when the man next to me, (who happened to be the fellow I had slept next to in the Erquinghem schools) was shot, and he died before the Stretcher Bearers had got him to the Dressing Station.

But this naturally made a dig harder than ever until I thought that my arms would drop out of their sockets.

We had to get to a certain depth before dawn for the trench had to be improved, and when the Germs spotted in the morning that we had been working, they would make a point of firing heavily all the next night in the hope of catching the working party.

We therefore kept going until about 4.30 am when we went back to our old trenches and turned in for a rest.

I had got nicely off to sleep (in spite of the wet) when at 5.15 am we were roused for the "stand to" which takes place before dawn and sunset each day, as this is the time it is most likely for an attack to be delivered.